'Super Gaggle' of Sea Knights

Sustained Khe Sanh's Battered Outposts

(Click on photo for a larger

image)

Definition of 'Super Gaggle':

Helicopter pilots refer to a formation flight of helicopters as a gaggle,

as in a 'gaggle of geese.' Therefore, when as many helicopters were

in the sky supporting Khe Sanh's besieged outposts, it was called a Super

Gaggle.

During the period from 24

February to 9 April 1968, the time frame of the "Super Gaggle", it was

my privilege to witness some of the most outstanding demonstrations of

sustained exceptional aeronautical skill and so many displays of unparalleled

courage that it would require a full length book to describe them individually

and adequately. Never in my career as a Marine aviator have I seen

such awesome responsibility placed on the shoulders of air crews, nor seen

such perfection in the briefing and execution of every minute detail of

flying combat missions.

J. A. "Al" Chancey

LtCol. USMC (Ret)

It was during this period that Khe Sanh was under siege

by a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) force which reached a peak of more than

30,000, or six times the number of US Marines which were garrisoned there.

Logistical support by ground over the Old Colonial Highway, or Route 9,

had become impossible due to the concentration of NVA forces and the monsoons

washing bridges away. Logistical support by air also became so hazardous

that only the plight of the Marines and the President's order to 'Hold

Khe Sanh' could justify the terrible losses of aircraft encountered in

resupply attempts.

Several

C-130s and C-123's were were destroyed on Khe Sanh's airstrip while attempting

to bring in the supplies required to 'Hold Khe Sanh.' (Click

here for additional photos and narrative of Khe Sanh) The enemy

siege became so tight that C-130s were finally prevented from landing and

were forced to resort to paradropping the supplies, some of which fell

to earth outside the perimeter of Khe Sanh and became sustenance for the

enemy. This still did not solve the problem of resupplying the ever

more besieged outposts around Khe Sanh, and helicopters sill had to brave

the heavy mortar, artillery, rocket and automatic weapons fire to carry

the critical supplies from Khe Sanh to the surrounding outposts.

The losses of helicopters in the attempt became so numerous it was obvious

a less costly method had to be developed if the outposts were to be held.

Several

C-130s and C-123's were were destroyed on Khe Sanh's airstrip while attempting

to bring in the supplies required to 'Hold Khe Sanh.' (Click

here for additional photos and narrative of Khe Sanh) The enemy

siege became so tight that C-130s were finally prevented from landing and

were forced to resort to paradropping the supplies, some of which fell

to earth outside the perimeter of Khe Sanh and became sustenance for the

enemy. This still did not solve the problem of resupplying the ever

more besieged outposts around Khe Sanh, and helicopters sill had to brave

the heavy mortar, artillery, rocket and automatic weapons fire to carry

the critical supplies from Khe Sanh to the surrounding outposts.

The losses of helicopters in the attempt became so numerous it was obvious

a less costly method had to be developed if the outposts were to be held.

An imaginative plan, the "Super Gaggle," was developed

to resupply the beleaguered outposts by helicopter from Dong Ha.

The plan had one very serious drawback, the heavy monsoon weather prevented

VFR (visual flight rules) through the high hazardous terrain between Dong

Ha and Khe Sanh. Another detrimental factor was the Khe Sanh TACAN

(tactical air navigation) and GCA (ground

controlled radar approach) facilities were inoperative most of the time

due to constant enemy bombardment.

The plan was a bold one that would require complex

planning involving large numbers of aircraft under instrument conditions

in a small area, one in which only perfection would be acceptable in its

execution. Fully aware of the aeronautical skill required and the

hazards that would be involved, the courageous pilots of HMM-364 readily

accepted this tremendous challenge.

The concept of operations involved picking up maximum

weight external loads at Dong Ha, climbing out under IFR (instrument flight

rules) on an obstacle clear radial of the Dong Ha TACAN

toward Khe Sanh with eight to ten aircraft, and rendezvousing over

Khe Sanh for a wave resupply of a designated outpost. If the flight

was not able to reach VFR (visual flight rules) on top, or find a break

in in the overcast to allow a spiral down through the cloud cover near

Khe Sanh, it would do a 180o turn climb to a pre briefed altitude

and return to either Quang Tri or Dong Ha for an instrument approach.

The instrument approaches utilized were either the TACAN which had helicopter

minimums

of a 600'ceiling and 1/2

mile visibility or the GCA which had helicopter

minimums of a 200' ceiling

and 1/4 mile visibility.

The worst of weather conditions prevailed throughout

most of the Khe Sanh emergency resupply operations. Many times the

pilots launched on their missions IFR when the weather at Dong Ha was well

below TACAN minimums and on several occasions even below GCA minimums.

It was hazardous, even without the threat of enemy fire, but the Purple

Fox air crews were determined not to leave their fellow Marines without

the means of combating the enemy forces. They continued to launch!

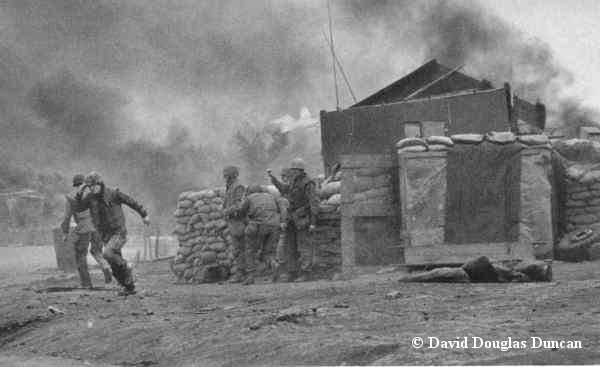

When the flight arrived over Khe Sanh the awesome task

was only beginning. The hilltop zones of 881S, 861, 861A,

558, 950 and 1015 (see maps) were generally

small and hazardous, they were well registered with enemy mortar, and the

area immediately outside the small perimeter was infested with automatic

weapons and snipers which were deadly to the slow moving vulnerable helicopters,

and no amount of fixed wing and artillery prep was able to silence all

of them. As the helicopters made their approach to  the

zones and hovered over it, as depicted here at Hill 861A to drop their

loads, automatic weapons opened up from all quadrants. Ground troops

around the zone dived into their trenches, for invariably the arrival of

the helicopters brought with them a barrage of mortars. In total

disregard for their own safety the pilots continued to make their approaches

to the zones erupting with mortar rounds and criss-crossed with automatic

weapons fire. When their designated landing zone blew up in front

of them, which was frequently, the courageous, determined pilots maneuvered

their aircraft left or right slightly and delivered their precious loads

anyway. The tighter the perimeters grew, and the more intense the

enemy fire, the more critical the ammunition, food, water, medical supplies

and replacement troops became. The Marines manning the outposts would

not be abandoned.

the

zones and hovered over it, as depicted here at Hill 861A to drop their

loads, automatic weapons opened up from all quadrants. Ground troops

around the zone dived into their trenches, for invariably the arrival of

the helicopters brought with them a barrage of mortars. In total

disregard for their own safety the pilots continued to make their approaches

to the zones erupting with mortar rounds and criss-crossed with automatic

weapons fire. When their designated landing zone blew up in front

of them, which was frequently, the courageous, determined pilots maneuvered

their aircraft left or right slightly and delivered their precious loads

anyway. The tighter the perimeters grew, and the more intense the

enemy fire, the more critical the ammunition, food, water, medical supplies

and replacement troops became. The Marines manning the outposts would

not be abandoned.

Frequently the flight commenced its approach when the

ground could only be seen through very small holes in the clouds and the

ceiling was very low, necessitating long low approaches exposed to close

range automatic weapons fire and sniper fire. Even when the hilltop

landing zones were covered with clouds the determined pilots would not

be deterred. On several occasions approaches were made and the mission

completed when the LZ was IFR. This was accomplished by flying low

up the valleys under the cloud base, entering the clouds at the base of

the hill, and air taxiing up the side of the hill while looking straight

down to maintain visual reference with the ground. This was hazardous

enough with only one plane involved, but with eight to ten aircraft making

the approach to the same zone under close range enemy fire it was sheer

madness, justified only by the urgency of the mission and the exceptional

skill of the pilots involved. These types of air crew actions epitomize

the understanding the Purple Foxes had of their mission in Vietnam which

was, "support the Grunts."

On

many occasions the crews, upon arriving at their designated outposts, would

see lifeless forms lying on the ground as depicted here at Hill 861A.

If a man lay uncovered upon the ground, he was a North Vietnamese soldier,

just fallen, soon to be buried by the Marines. If a man on the ground

or litter had been covered with a poncho, he was a Marine killed in action

and awaiting evacuation to the rear, and the journey to his family.

Not much more could be done, in war, for the dead of either side.

Therefore, when the initial loads from Dong Ha had been delivered for a

particular outpost there were still the dead and other Marines requiring

immediate medical assistance which needed to be evacuated to Khe Sanh and

from Khe Sanh to Dong Ha. Many times these crews would pick up, or

deliver, medevacs at Khe Sanh with mortars and artillery shells falling

all around them. If the rounds got too close for them to remain in

the zone the pilot would lift out, circle once and immediately land again

to complete his mission. If the lead aircraft was significantly damaged

the chase aircraft, without hesitation, would continue where the other

aircraft and crew left off.

On

many occasions the crews, upon arriving at their designated outposts, would

see lifeless forms lying on the ground as depicted here at Hill 861A.

If a man lay uncovered upon the ground, he was a North Vietnamese soldier,

just fallen, soon to be buried by the Marines. If a man on the ground

or litter had been covered with a poncho, he was a Marine killed in action

and awaiting evacuation to the rear, and the journey to his family.

Not much more could be done, in war, for the dead of either side.

Therefore, when the initial loads from Dong Ha had been delivered for a

particular outpost there were still the dead and other Marines requiring

immediate medical assistance which needed to be evacuated to Khe Sanh and

from Khe Sanh to Dong Ha. Many times these crews would pick up, or

deliver, medevacs at Khe Sanh with mortars and artillery shells falling

all around them. If the rounds got too close for them to remain in

the zone the pilot would lift out, circle once and immediately land again

to complete his mission. If the lead aircraft was significantly damaged

the chase aircraft, without hesitation, would continue where the other

aircraft and crew left off.

Evacuating the dead from Khe Sanh to Dong Ha

1stLt. Bruce M. Geiger, USMC, of Golf Battery, 65th

Artillery describes his flight to Khe Sanh and more. "My flight

from Phu Bai was a memorable occasion. We were briefed by the crew

chief to expect heavy ground fire including .50-caliber machine gun, mortar,

and artillery rounds. The crew chief had us lay our gear bags on

the floor beneath us to shield our bodies from ground fire that might penetrate

the underside of the chopper. Needless to say, we were all very nervous

and "puckered" at the thought of .50-caliber rounds ripping through the

thin underbelly of the chopper beneath us! We would circle down through

a heavy cloud cover and have only a few seconds with the tailgate on the

ground to disembark with all our gear. As we began our descent, we

saw tracer rounds streaking past the windows through the clouds.

The crew chief shouted that we would have less than ten seconds on the

deck, and we had better be off the ramp or know how to fly!

Upon landing there were mortars and artillery rounds

exploding all around the landing area. The crew chief lowered the

ramp and we were dumped out like a heap of garbage from the rear of a sanitation

truck. We scattered like rats for the nearest trench line or

bunker and waited in sheer terror for what seemed like an endless barrage

to be over. The chopper disappeared back into the clouds.

Khe

Sanh was a very bad place then, but the airstrip was the worst place in

the world. It was what Khe Sanh had instead of a V-ring, the exact,

predictable object of the mortars and rockets hidden in the surrounding

hills, the sure target of the big Russian and Chinese guns lodged in the

side of CoRoc Ridge, eleven kilometers away across the Laotian border.

There was nothing random about the shelling there, and no one wanted anything

to do with it. If the wind was right, you could hear the NVA .50-calibers

starting far up the valley whenever an aircraft made its approach to the

strip, and the first incoming artillery would precede the landings by seconds.

If you were waiting there to be taken out, there was nothing you could

do but curl up in the trench and try to make yourself small, and if you

were coming in on the aircraft, there was nothing you could do, nothing

at all."

Khe

Sanh was a very bad place then, but the airstrip was the worst place in

the world. It was what Khe Sanh had instead of a V-ring, the exact,

predictable object of the mortars and rockets hidden in the surrounding

hills, the sure target of the big Russian and Chinese guns lodged in the

side of CoRoc Ridge, eleven kilometers away across the Laotian border.

There was nothing random about the shelling there, and no one wanted anything

to do with it. If the wind was right, you could hear the NVA .50-calibers

starting far up the valley whenever an aircraft made its approach to the

strip, and the first incoming artillery would precede the landings by seconds.

If you were waiting there to be taken out, there was nothing you could

do but curl up in the trench and try to make yourself small, and if you

were coming in on the aircraft, there was nothing you could do, nothing

at all."

The air crews of HMM-364 arose each morning before

daylight, flew two to five of these trips per day into Khe Sanh and its

outposts, and returned after dark. Any one of these days, or any

one of the trips for that matter, may well have merited a significant award

for gallantry under extreme conditions. The fact is though, that

the same crews willingly and courageously flew these same missions day

after day for 45 consecutive days, with only an occasional Andy break,

without thinking about awards, but rather thinking of the Marines who needed

their support. During this period the pilots of HMM-364 flew 422.2

hours of actual instrument time and 246 radar departures and

approaches. Much of this was with maximum weight external loads.

Only those who have done it can appreciate the difficulty encountered in

flying under actual instrument conditions with a heavy external load rocking

the aircraft 15o from side to side and pitching the nose up

and down 10o to 20o. It was a constant fight

to combat vertigo (or spatial disorientation) induced by the gyrations

of the helicopter in response to the swinging load. Recovery from

these conditions, under actual IFR conditions, is rendered even more difficult

by the basic instability of the helicopter itself.

The strain of the furious pace and the constant exposure

to extreme danger was mirrored in the eyes of the weary crews, but not

a complaint was heard. The fact that they continued to contribute

willingly and with determination was a tribute to their stamina, courage

and exceptional aeronautical skill. Through their valiant efforts,

and only through their efforts, were the outposts around Khe Sanh sustained

and provided with the means of holding the area and maintaining constant

surveillance of the enemy until relief could come by road and break the

siege on 9 April 1968.

Information provided by:

J. A. (Al) Chancey, LtCol. USMC

(Ret)

War Without Heroes, Harper and

Row, 1970

David Douglas Duncan

John Sabol, Jr., former Sgt. USMC

Boeing Helicopter News, January

1969

Bruce M. Geiger, former 1stLt.

USMCR

Federation of American Scientists

Back Browser or History

Index or Home

Several

C-130s and C-123's were were destroyed on Khe Sanh's airstrip while attempting

to bring in the supplies required to 'Hold Khe Sanh.' (Click

here for additional photos and narrative of Khe Sanh) The enemy

siege became so tight that C-130s were finally prevented from landing and

were forced to resort to paradropping the supplies, some of which fell

to earth outside the perimeter of Khe Sanh and became sustenance for the

enemy. This still did not solve the problem of resupplying the ever

more besieged outposts around Khe Sanh, and helicopters sill had to brave

the heavy mortar, artillery, rocket and automatic weapons fire to carry

the critical supplies from Khe Sanh to the surrounding outposts.

The losses of helicopters in the attempt became so numerous it was obvious

a less costly method had to be developed if the outposts were to be held.

Several

C-130s and C-123's were were destroyed on Khe Sanh's airstrip while attempting

to bring in the supplies required to 'Hold Khe Sanh.' (Click

here for additional photos and narrative of Khe Sanh) The enemy

siege became so tight that C-130s were finally prevented from landing and

were forced to resort to paradropping the supplies, some of which fell

to earth outside the perimeter of Khe Sanh and became sustenance for the

enemy. This still did not solve the problem of resupplying the ever

more besieged outposts around Khe Sanh, and helicopters sill had to brave

the heavy mortar, artillery, rocket and automatic weapons fire to carry

the critical supplies from Khe Sanh to the surrounding outposts.

The losses of helicopters in the attempt became so numerous it was obvious

a less costly method had to be developed if the outposts were to be held.