How to Get Shot Up and Not Know About It

By Daryl D. Riersgard, 1stLt. USMCR (Vet)

This is an account from 34 years ago. As the

title suggests it is not easy to get a personal wound in combat and not

realize it for 45 minutes. This is my best attempt at reassembling

the facts of the incident from 27 October 1970.

There were few aircraft flyable this date, possibly

only three being Bureau #s 154838 (YK-18??),

154027 and 154815. The last two were assigned the medevac mission

for the day with Bureau # 154027 flown by 1stLt. Steve

"Injun" Kux and Maj. N. R. Van Leeuwen,

and Bureau # 154815 piloted by 1stLt. Peter T. "Pete"

Baron and 1stLt. Larry J. "Harvey Wallbanger"

Thompson. The weather conditions this morning gave us low ceilings

and light rain. Forced to fly low, Lts. Baron and Thompson encountered

intense enemy fire and received numerous hits which resulted in a forced

landing before reaching Marble Mountain Air Facility. Their crew

was picked up by Lt. Kux and Maj. Van Leeuwen and delivered to Marble Mountain.

This story has to do with a replacement

crew for the medevac mission which was assembled quickly after the battle

damage sustained by Bureau # 154815 and consisted of 1stLt.

Gary "Bofus" Denton, the pilot, me, Daryl

Riersgard as his copilot and Cpl. Gary Radliff

the crew chief. I don't recall the names of the aerial gunners

or the corpsman. Our crew was assembled, briefed and airborne by

mid-morning. Due to the number of medical evacuations required we

did not join up with Lt. Kux's aircraft, but rather each individual aircraft

were sent to various locations by DaNang DASC. We each had gun ship

support.

Our first medevac mission included

a routine pickup approximately 25 miles south of Marble Mountain.

Our second assignment was trickier as it was atop Hill-270 South.

For those that recall this zone, there was never enough room to place all

three wheels on the ground so we tended to one or two wheel landings while

maintaining a partial hover.

As we approached this mountain

top zone, Lt. Denton was at the controls. Our approach was flatter

than normal as we had to fly in under the base of the clouds. Our

approach was from the north west side of the landing zone, and was normal

until around 200 to 300 feet above the zone. Our approach went from

normal to catastrophic in just an instant. I recall a loud noise,

perhaps an explosion, followed immediately by a rotor system intermesh.

I have a clear memory of seeing a rotor blade fly off on the left side

(usually a bad sign). It looked like a boomerang flying out and away

from the helicopter. In that brief instant we went from a perfectly

good helicopter to a 26,000 pound rock. Our approach path was such

that we overshot the zone and crashed on the south east slope of the hill.

I estimate we impacted the ground about 50 yards past the zone where the

Marines were positioned.

I remember the ground coming

up fast, but I don't recall the actual impact. I was knocked out

when we hit and based upon the crescent shaped piece of skin missing from

under my chin, I assume the bullet bouncer came up while my head was coming

down the upper cut put me to sleep for a few seconds.

I do recall waking up as the

helo was doing a wild roller coaster ride down the mountain. The

distance from the first impact to the final resting place was less than

100 yards. This wild ride would have lasted a lot longer except for

some very large boulders that stopped us in our tracks. I believe

I was knocked out a second time when we hit the boulders. When I

woke up I recall the aircraft being on its left side. My first instinct

was to get out through the normal crew's entrance. I decided that

wasn't such a good idea when I saw flames in the cabin section. I

elected to depart the wreckage through my emergency side window, popped

the handle and the window section fell away. My exit route was clear

now as I was looking down into a five foot gap in the rocks. I released

the side panel of the armored seat, released the seat belt and shoulder

harness and rolled out. This would have been a cool exit except that

I forgot to release my helmet radio pig tail connection. That mistake

gave me a good head jolt before I hit the ground.

When I crawled out of the rocky

hole, I came around the nose section of the aircraft and had my first good

look at the mess. A good portion of the helo was engulfed in flames.

I saw the Corpsman crawl out of crew's door, on what was now the top part

of the wreckage. Within a few seconds others followed. It was

an orderly process as we assisted each other to safety. I don't recall

the total on board in excess of the five crew members , but I believe we

still had the routine evacuees on board from the previous pickup site.

By the time we had everyone out

of the wreckage I recall a few rounds cooking off from the heat.

Now that the cabin was evacuated we turned our attention to getting the

pilot out. For those who recall, Gary "Bofus" Denton was a big guy.

My first impression was that Gary had died in the crash. The top

portion of the cockpit had caved in around his head. There was also

a large quantity of red fluid on top of us. My first thought was

that it must be blood, but later it was apparent that we both had gotten

a hot bath of hydraulic fluid. He was still unconscious and very

difficult to pull up and out of his rescue side window that was now the

top of the wreckage pile. As three of us were lifting him out he

began to regain consciousness. Apparently there was not enough fuel

spilling to sustain the fire since the helicopter was not totally consumed

by fire.

While all this was going on there

was a decent fire fight overhead. The Marines on the hill top were

firing at the enemy positions who most likely shot us down. Our next

challenge was to crawl up a very wet mountainside to the relative safety

of the Marines on Hill-270S. Some of the men could help themselves,

others needed assistance getting to the top. It was tempting to grab

an M-16 and join the fire fight except we all had our hands full.

It seemed like we would take two steps up and slide back one on the steep,

wet slope. As we approached the top of the mountain, ground Marines

were coming down to meet us and to assist us the remainder of the way up.

While all this was going on,

our Huey gun cover made a memorable move. That crew flew to the nearest

fire support base and dropped off the entire crew and machine guns leaving

only the pilot and the copilot aboard. This lightened their aircraft

to make them capable of extracting the most seriously injured from our

crash or wounded of the grunts. That crew was back in the zone within

a matter of minutes and evacuated the most critical. The rest of

us had to wait for Steve Kux to finish the rescue. At the time of

our crash he was refueling at Marble Mountain and then broke the air speed

red line limitation getting back to us.

Now to the title of this story

. . . .

I recall after helping lift some

of the evacuees into the Huey, I noticed that my left boot was covered

with blood. The assumption was the blood belonged to one of those

Marines we had just loaded into the Huey. I wiped the blood off on

the back of my flight suit pant leg. I then sat down to recount this

wild adventure. After a few minutes, now nearly 45 minutes after

the crash, I looked down and noticed my boot was again covered with

blood. When I pulled up the left leg of the flight suit I saw that

I had a bullet hole through my calf and out my shin. It was a minor

wound, but it seemed odd that I had no recollection thanks to all the other

excitement going on.

Steve Kux landed a short time

later and flew the remainder of us to the 95th Evacuation Hospital for

medical assistance.

I flew back to the crash site

a few days later, as a passenger, and found the copilots emergency hatch.

The Plexiglas was missing from the frame; however, it was easy to identify

three different bullet holes in the frame of the emergency escape window.

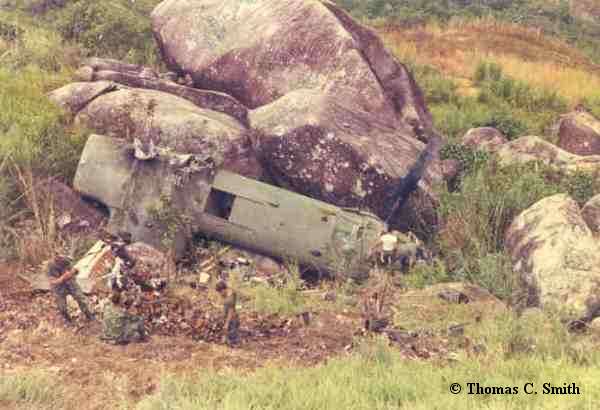

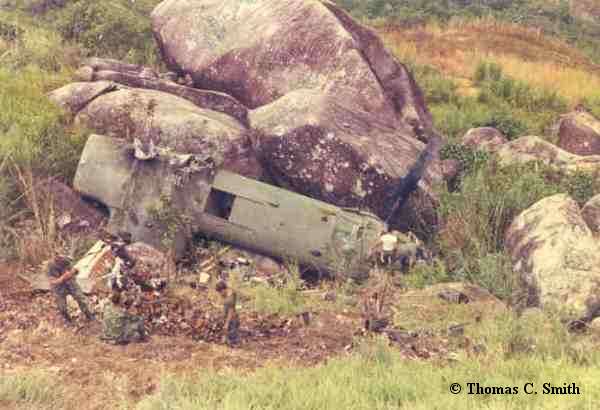

Recover crew salvaging radios and other reusable parts

from the crash site a

day or so later.

Capt. Art Blades, lower right, examines YK-18.

Wonder how many more times YK-18, would have rolled

over if the huge rocks

hadn't been there?

Back Browser or Home

.